When Papi Diouf arrived in Connecticut in 2011, he was immediately struck by one thing: the cold.

“The breeze, the white, the cold, the ice,” said Diouf, then 13 years old. “That hit me first — and now I know I’m not in Senegal no more.”

A native of Thiès, Senegal, Diouf came to the United States after being offered a scholarship to play soccer for Avon Old Farms, a boarding school just outside of Hartford, Connecticut.

Soccer runs in Diouf’s blood. His father grew up playing the sport and his brother plays professionally in Sweden.

He never imagined leaving his home in Senegal, but when the opportunity arose, it was his mother who gave Diouf — a self-proclaimed “mommy’s boy” — the motivation to do so.

“She told me, ‘If you love me, you’re going to go do what you got to do,’ ” he recalled. In that moment, he decided, “You know what? I’m out because I would do anything for you.”

The words of his mother stuck with Diouf as he told her goodbye at the airport. Doubts and second thoughts began to creep in. But with tears in his eyes, Diouf reminded himself, “You can do this.”

Diouf had difficulty adjusting to life in the Northeast. He remembered having difficulty breathing the piercing cold Connecticut air. Even American food made him sick. He said he cried almost every night and begged to go back home in his first year. Diouf also didn’t speak English, which hindered his performance in the classroom and on the soccer pitch.

“It was so painful being on the field, playing with a friend, not knowing the language,” Diouf said. “Sometimes you have a chance to get the ball to score, but they don’t give it to you because you don’t ask, because you don’t know how to tell them to pass the ball.”

After an extended stay at a camp school in New Hampshire to focus on learning English, Diouf returned to Avon able to communicate with his peers.

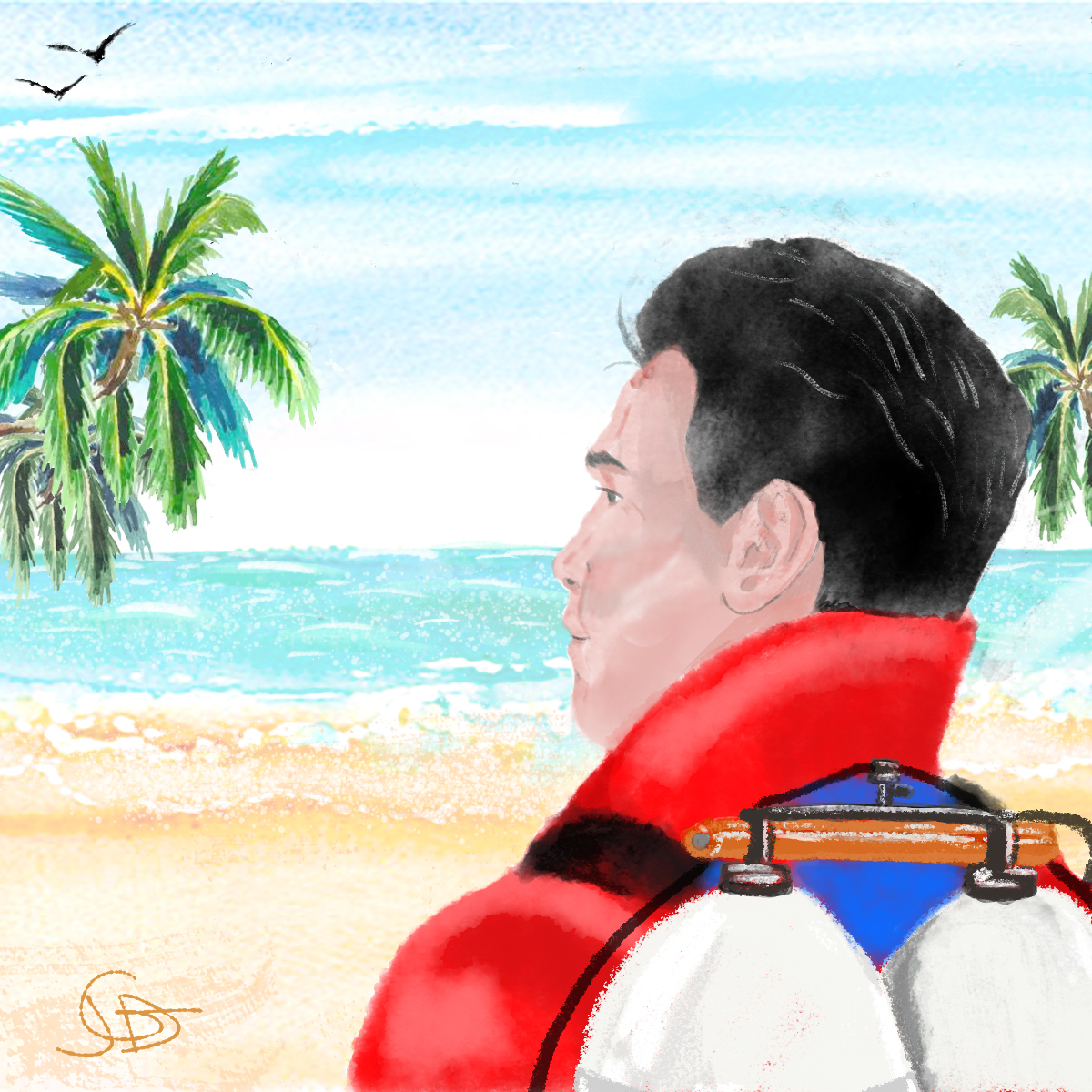

Papi Diouf went from not being able to ask for the ball in English to earning a bachelor’s degree in communications. (Photo courtesy of Papi Diouf.)

Despite his difficulties, and despite being one of only a handful of non-white students at the boarding school, Diouf said he never felt alienated or isolated. He instead found himself welcomed with open arms by his classmates and the staff at Avon Old Farms. They seemed to understand the sacrifices Diouf made to be there.

“At that point I wasn’t thinking, ‘where’s the black people?’ ” he said. “I’m just seeing everybody as a family.”

Diouf struggled with homesickness, but he was able to find comfort and familiarity in the home of Peter Rice, his high school coach. Rice’s wife, Tieba, is from Togo and the couple lived in the West African country for a number of years, Diouf said. They would cook traditional African dishes such as white rice with fish, tomato sauce, or chicken, which gave him a piece of home whenever he needed.

The Rice family took Diouf in as one of their own. He would go to them whenever he needed to talk things out, which was crucial to him in his teenage years. They made the Senegalese teenager at home in Connecticut despite being more than 3,500 miles away from it.

“Family isn’t only blood. Family is who you can relate with and tell them what you think, and who can understand you … because of who you are.”

Papi Diouf

Diouf spent three years at Avon before moving to Kentucky in 2014 to play for the University of Louisville, where he scored a goal in his first match.

Diouf then transferred to California State University, Northridge after his freshman year, where he scored the fastest goal in Big West conference history — eight seconds into an August 2016 match.

He recently graduated with a bachelor’s degree in communications.

Diouf is still training in hopes of playing professional soccer. If no team signs him, Diouf’s backup plan is to become a sports agent and help young African athletes get the kind of opportunities that he did.